- 2 January 2016

- Magazine

-

(음악) 굶주림 속에서 연주된 쇼스타코비치의 교향곡음악/음악 2016. 1. 2. 21:47

출처: http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-34292312

Shostakovich's symphony played by a starving orchestra 밥도 제대로 못 먹은 단원들이 연주한 쇼트타코비치의 교향곡

St Petersburg Academic Philharmonia

St Petersburg Academic PhilharmoniaKarl Eliasberg conducting on 9 August 1942 In the summer of 1942, Leningrad was starving. It had been under siege and bombardment by German forces for nearly a year. And yet an orchestra managed to perform a new symphony by the composer Dmitri Shostakovich, and broadcast it across the city. 1942년 레닌그라드는 먹을 것이 없어 굶주리고 있었다. 거의 1년간 독일군에게 포위 당한 채 폭격 당하고 있었기 때문이다. 그런 상태에서도 한 오케스트라가 디미트리 쇼스타코비치의 교향곡을 연주하는 장면이 그 도시에 방송되었다.

When conductor Karl Eliasberg received instructions to rehearse Shostakovich's Seventh Symphony he had a problem. 지휘자 칼 엘리아스버그가 쇼스타코비치의 7번 교향곡을 리허설한다는 소식을 접했을 때, 그는 문제를 하나 안고 있었다.

After a performance the previous December of Tchaikovsky's 1812 Overture - which depicts the Russia's victory over Napoleon's invading army - the only remaining orchestra in the city, the Leningrad Radio Orchestra, had shut down. 이 도시에 유일하게 남아있던 레닌그라드 라디오 오케스트라가 러시아의 나폴레옹에 대한 승리를 그린 차이코프스키의 1812년 서곡을 연주한 후, 문을 닫았다.

A note in the ensemble's log records: "Rehearsal did not take place. Srabian is dead. Petrov is sick. Borishev is dead. Orchestra not working." 이 오케스트라의 일지에 적힌 메모: "리허설은 못했다. 스라비안은 타계했다. 페트로브는 몸이 안 좋다. 보리세프는 타계했다. 오케스트라는 연주 불가."

So it was no surprise that when Eliasberg recalled his musicians for a rehearsal, only 15 turned up. 이런 상태에서 지휘자 엘리아스버그가 리허설 하자고 단원들을 소집하니 겨우 15명만 나왔다는 건 놀라운 일이 아니다.

Among them was oboist Ksenia Matus. "When we began rehearsals for the performance, I had to take my oboe to be repaired," she recalled years later. "I went back to collect it and asked how much I owed. The repairman said "just bring me a pussycat". He said he preferred their meat to chicken." 참석자 중에는 오보에 연주자 크세니아 마투스가 있었다. "우리가 리허설을 시작했을 무렵, 전 오보에를 수리공에게 맡겼어요."라고 후에 그녀는 회상했다. "저는 악기를 회수하러 수리점에 가서 얼마냐고 물었죠. 그 사람은 '고양이 한 마리만 가져다 주세요'라고 말하더군요. 자기는 닭고기보다 고양이 고기가 더 좋다고 하더군요.

The first rehearsal broke up after just 15 minutes, as the small band of survivors had so little energy. 첫 리허설은 15만에 끝났다. 모인 단원들이 너무 기력이 달렸기 때문이다.

"That orchestra was consisting of players who were victims of bombings and hunger and starvation and they were barely able to hold their instruments to play," says Soviet-born conductor Semyon Bychkov. 단원들은 폭격을 당했거나 배고프거나 굶주렸다. 그래서 거의 자기 악기를 가지고 소리를 낼 수 조차 없었다.

One trumpeter offered Eliasberg a profound apology after failing to produce a single note. 한 트럼펫 주자는 음표 하나도 소리를 낼 수 없어 지휘자에게 사과를 하기도 했다.

Find out more

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSemyon Bychkov spoke to Newshour on the BBC World Service - listen to his interview here

Ksenia Matus featured on Witness, also on the BBC World Service - listen to the programme here

Leningrad and the Orchestra that defied Hitler, including excerpts of the symphony conducted by the composers's son, is on BBC Two on Saturday at 9.10pm - the programme will be available online in the UK after broadcast

Reinforcements were needed.

The Soviet authorities sent an order down the battle lines, ordering any musicians to report for rehearsal. Men came from military camps, and would rehearse between assignments.

It's possible that Shostakovich, who worked at the Leningrad conservatoire, had started work on the symphony before the German invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, but he began to work on it with "inhuman intensity", as he put it, in the weeks that followed.

He remained in the city after the start of the siege in September - a piano recital of the first movement, which he gave to a select group of friends, was interrupted by an air raid.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe was finally ordered to leave on 1 October.

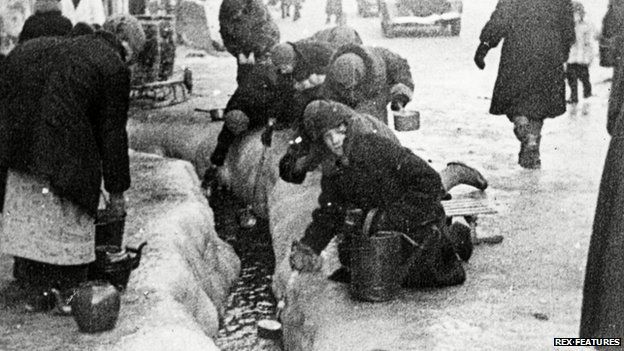

With supplies cut off, Leningraders were eventually reduced to eating rats, horses, cats and dogs. There were also reports of cannibalism. And while hunger plagued the residents the Luftwaffe attacked them from the air, carrying out frequent heavy raids.

Survivors of the pitiless winter of 1941-42 in Leningrad recall bodies lying in the street, with nobody to bury them.

Rex Features

Rex FeaturesEliasberg imposed strict discipline to get his players into shape. Wind players in particular might get light-headed or keel over when they played. But he would cut the bread ration of any players who performed badly or arrived late for a rehearsal - even if they had been delayed burying a dead family member.

The instrumentalists worked together six days a week, and piece by piece the symphony came together. The day of the performance - 9 August 1942 - arrived with the orchestra having played it all the way through only once, at a dress rehearsal three days earlier.

"Just before, the Soviet army did a very vicious bombardment of the German army lines in order to silence the German guns, so the concert could take place without being interrupted," says Bychkov.

Loudspeakers were set up throughout the city to relay the performance not only to the population, but to the German troops as well.

One of those in the audience was 18-year-old Olga Kvade, whose father and grandfather had both died at the beginning of the year. Now in her nineties, Kvade remembers the event clearly.

"The chandeliers were sparkling, It was such a strange feeling. on the one hand it couldn't be possible - the blockade, burials, deaths, starvation, and the Philharmonic Hall - it was just so incredible," she says in a BBC documentary to be screened on Saturday.

Olga Kvade describes watching the Leningrad concert "The only thing we feared was that the Germans would start bombing us. I was thinking, 'God, let us listen to it to the end.' But then Eliasberg came out, the orchestra stood up, and they played. Everyone was starving, but they were all dressed up in bow ties.

"For some reason I immediately thought of Papa. Papa loved good music. He himself played and he'd been teaching me. And I remembered how he would take me to the Philharmonic Hall, and it seemed to me that somehow he was listening too.

on the one hand I wanted to cry but at the same time there was a sense of pride. 'Damn you, we have an orchestra! We're at the Philharmonic Hall so you Germans stay where you are!' We were surrounded by Germans. They were shelling us, but there was this feeling of superiority."

The end of the concert was greeted at first with silence.

"And then suddenly there was a storm of applause," recalled Ksenia Matus. "A girl came up from the audience with a bunch of flowers. She gave them to the conductor. Can you imagine fresh garden flowers during the blockade? It was unbearably joyful."

St Petersburg Academic Philharmonia

St Petersburg Academic PhilharmoniaShostakovich meets Eliasberg and players at a 20th anniversary performance in 1964 - Ksenia Matus is seated on the left Shostakovich had dedicated his symphony to the people of Leningrad, who went on to endure another year and a half of siege before the Soviet army broke through the encirclement in January 1944.

By then about three-quarters of a million civilians are estimated to have died in the city.

When Bychkov hears the symphony he is moved to think of those "who have lived it, survived it, and who managed to preserve their humanity" - including his own mother.

"When I grew up I would hear occasionally little snippets of what she lived [through]," he says. "She would never tell me big stories. But she would tell me occasionally a little episode here and there."

One such episode found his mother sitting in her cellar during a German bombing raid. "The bomb fell on the building, through the roof and went all the way to the cellar where they were", he says. Miraculously, it did not explode.

The Leningrad symphony

- Shostakovich started work on the symphony in July 1941, at the age of 35, and completed in Kuibyshev in December

- It was premiered in Kuibyshev in March 1942, and performed in Moscow shortly afterwards

- Played at the BBC Proms in London in June 1942 - exactly a year after the German invasion of the USSR

- New York premiere under Arturo Toscanini in July 1942, Leningrad premiere in August

- The work requires a huge orchestra including eight horns, six trombones and two harps

In the 1950s, Eliasberg had a visit from a group of East German tourists.

"They went to see him and they told him they [had been] soldiers in the German army just on the edges of the city. They were listening to the broadcasts of that orchestra concert, including the seventh symphony of Shostakovich," Bychkov says.

"They were hungry too. They were frightened as well. A lot of them didn't want to be there but had no choice. A lot of them got killed."

The men told Eliasberg that when they heard the performance of Shostakovich's symphony they understood that a city of people who showed such spirit would not capitulate. one is reported to have said that his comrades shed tears when they heard the music.

"Here were people representing the opposing side of the war, who needed music just as badly as the ones for whom it was composed," says Bychkov. "Because in the end it was composed for humanity. And the best proof is that today we still need it, we are still listening to it."

Eliasberg would perform the symphony again in Leningrad on a handful of occasions. But his wartime concert would not be the launch of a stellar conducting career, nor would he be feted as a hero of Soviet culture. Instead he died, all but forgotten, in 1978.

The music he performed has endured, however. It has become one of Shostakovich's best-known works, often referred to, appropriately, as the Leningrad Symphony.

'음악 > 음악' 카테고리의 다른 글

(음악/오디오) 드미트리 쇼스타코비치 7번 교향곡 (0) 2016.01.02 (음악/오디오) 차이코프스키 1812년 서곡 (0) 2016.01.02 (음악/동영상) 백세인생 / 가수 이애란 (0) 2015.12.19 (음악/오디오) 한순 시인의 노래 "어쩌다 나는" (0) 2015.11.17 (음악/동영상) You Raise Me Up - Josh Groban (with lyrics) (0) 2015.07.03