- 8 hours ago

- Australia

-

(호주) 왜 맹인 교수는 아내의 얼굴을 잊기로 결심했는가?국제문제/오세아니아 2016. 2. 15. 18:49

Why a blind professor decided to forget his wife's face BBC News

동영상 출처: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KX8X28SfY2Q

기사 출처: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-australia-35557262

Why a blind professor decided to forget his wife's face

In Notes on Blindness theologian John Michael Hull speaks about returning home to Australia after losing his sight An Australian man decided to make himself forget what the world looked like in order to come to terms with his blindness. His detailed descriptions of losing his sight are now the subject of a feature-length documentary, writes Ed Gibbs.

Forgetting what your loved ones look like hardly sounds like a remedy for well-being.

But that's precisely what author John Michael Hull had to do, if he was to accept his blindness.

The son of a Methodist preacher and a lifelong theologian and academic, Prof Hull had been losing his sight since childhood, following a botched cataract operation in his childhood home of Corryong in Australia's Victoria state.

Devastating homecoming

Archer's Mark

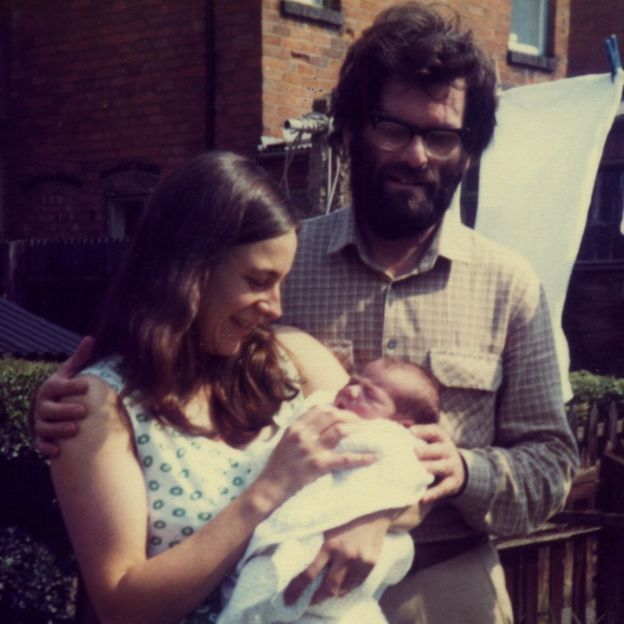

Archer's MarkProf John Hull had five children, including four with his second wife Marilyn But it wasn't until 1980, when Prof Hull was in his mid-forties, that his eyesight disappeared for good. A trip home to Australia from the UK, where he was based, was meant to ease his mind, but instead it plunged him into despair.

"It was the darkest moment of his life," Prof Hull's wife, Marilyn, says. "He expected to enjoy the environment, to enjoy remembering the things he'd loved so much growing up - where he went to school, the coast, being surrounded by his family en masse.

"But he felt totally alienated by not being able to see any of it, and having the distortions of memory. It was extremely painful.

"So when he came back from Australia, he thought, 'Right, I have to become a blind person. I can't live in two worlds. I have to listen and touch, and essentially forget the visual.' Which meant having to forget what I looked like."

Marilyn, who was expecting the couple's first child at the time, suggested her husband throw himself into his work. Colleagues and students helped provide reading material on audio cassettes.

Prof Hull then came up with the idea of articulating his experience of going blind on tape. When the tapes were later published, neurologist Oliver Sacks hailed the results as definitive: "The most extraordinary, precise, deep and beautiful account of blindness I have ever read. It is, to my mind, a masterpiece," he said.

Rebirth and renewal

Filmmakers Peter Middleton and James Spinney were similarly taken by Hull's account of his experience. After seeking out the father-of-five in 2010, the pair convinced the lecturer - by now in his mid-seventies - to share the original recordings with them.

The tapes contain diary entries from him coming to terms with going blind, as well as intimate moments at family gatherings such as Christmas, birthdays and baptisms.

"They really map out John's journey from a position of grief and loss and frustration, through to ... perceiving blindness as an enormous gift, and this rebirth and renewal of his personality," Mr Middleton says.

on top of that, we were also interviewing John and Marilyn over the course of the last five years, interweaving that perspective with this period of adjustment, 30 years on."

Archer's Mark

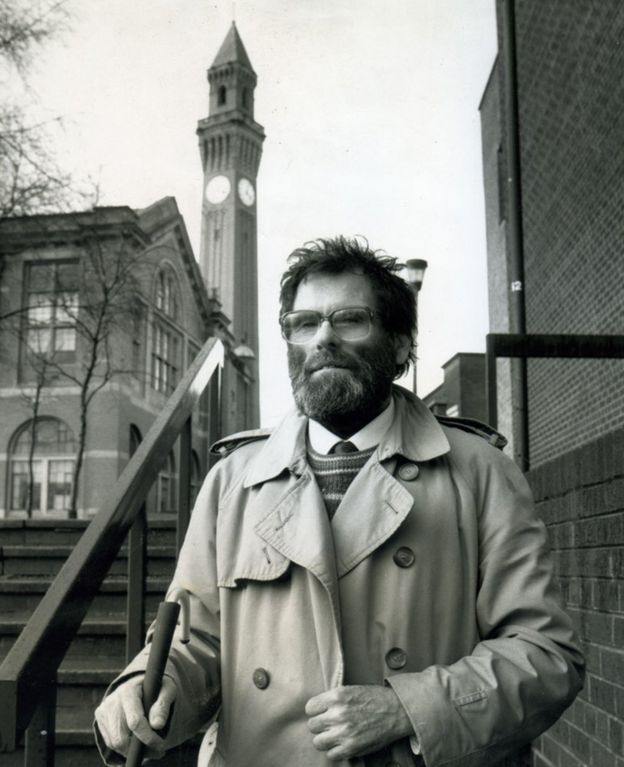

Archer's MarkProf Hull was a respected theologian who taught at the University of Birmingham In order to visualise the material, the filmmakers cast two lookalike actors, Dan Renton Skinner and Simone Kirby, to lip-sync to the couple's recorded audio.

"The actors were able to inhabit John and Marilyn - especially Dan, who had to act without his eyes," Mr Middleton says.

"The role was restrictive and isolating for him. For John and Marilyn, it was like reopening an old wound, one that they'd moved on from. John was a very different person to the one from this period. So it took time to get it right."

A life of integrity

Prof Hull, who died suddenly last July, aged 80, found revisiting his past both challenging and rewarding, Marilyn says.

"John didn't keep diaries, so this was a one-off," she says. "And when he came through this period, well, he stopped making the diaries. He didn't need to do it anymore.

"It was an incredibly busy and traumatic time. It was very difficult, because he was a person of enormous personal joy and mischief and fun.

"He had a very positive personality. After that trip to Australia, he decided, 'I'm going to live my life with integrity as a blind person.' Which was, essentially, the beginning of his recovery."

The couple went on to live a happy and fulfilled life, Marilyn said, a fact born out in the feature-length film, which had its world premiere at last month's Sundance film festival in Utah. If Prof Hull were alive, Marilyn says, he would be thrilled with the result.

"Peter and James became practically members of the family," she says. "He was delighted with what they were doing with the material.

"These are wonderful, creative pieces. They record an experience that's not just about blindness, but also about loss and a reshaping of consciousness, which is a reshaping of one's humanity, really. I feel very proud that John's story has somehow contributed to that."

'국제문제 > 오세아니아' 카테고리의 다른 글

(호주) 호주 추기경 아동학대 문제에 대한 견해를 밝히고자 법정에 선다 (0) 2016.02.29 (남태평양/파푸아뉴기니) 파푸아뉴기니 교도소 죄수 11명 탈옥 중 사망 (0) 2016.02.27 (호주) 호주의 드문 화산 폭발 영상 (0) 2016.02.02 (호주) 토네이도로 인한 강풍이 호주 시드니를 강타하면서 주택지붕 날려버리다 (0) 2015.12.16 (뉴질랜드) 국기 선택 위한 뉴질랜드 국민투표 진행 (0) 2015.11.21