- 12 March 2016

- Science & Environment

-

(과학) 화성탐사과학과 테크놀로지/과학 2016. 3. 14. 23:05

출처: http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-35767882

Mars mission targets Monday launch 화성탐사 3월14일 월요일 발사 목표

ESA

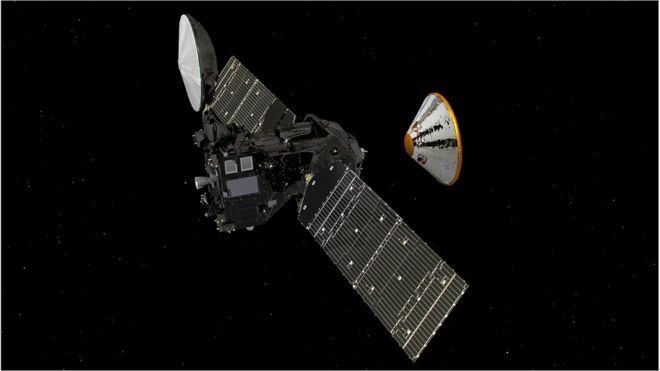

ESAArtist's impression: It will be a seven-month cruise from Earth to Mars 지구에서 화성까지 비행시간 7 개월 소요 All looks good for an on-time launch of Europe's mission to Mars.

A joint venture with Russia, the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) is set to launch atop a Proton rocket from Baikonur, Kazakhstan, on Monday. (TGO는 3월14일 월요일 카자흐스탄 바이코누르에서 Proton로켓 발사 예정)

The satellite will try to detect and characterise the marginal constituents of the planet's atmosphere. (1) 이번 화성탐사의 대략적 목적: 화성 대기권의 구성요소를 찾아내 분석하는 것)

A key quest is to understand methane, a gas that has an unexpected persistence and which some have speculated could hint at the presence of microbial life. (2) 이번 화성탐사의 구체적 목적: 미생물체의 존재를 암시한다고 일부 학자들이 주장하고 있는 메탄 가스에 대해 상세히 파악하는 것. (microbial life: 미생물체)

Lift-off of the Proton is scheduled for 15:31 local time (09:31 GMT). (lift-off는 명사로 우주선발사, lift off는 동사로 발사하다)

"We've had a good launch campaign to date - no real issues," said Walter Cugno from the lead European contractor, Thales Alenia Space.

"All the preparation milestones have been achieved as per the nominal schedule," he told BBC News. (preparation milestones: 준비단계들) (as per nominal/usual: 의레 그렇듯) (nominal: 명목상의)

ESA/S.CORVAJA

ESA/S.CORVAJAThe Proton has been erected on the pad ready for the launch It will take 10 hours for the Proton's Breeze-M upper-stage to boost the ExoMars TGO into just the right trajectory to go to the Red Planet. (밝은 하늘: 화성까지 날아가는데 필요한 궤도 진입에 소요되는 시간 10시간. 그 궤도는 지구탈출 속도를 초속 12키로로 계산하면 지구상에서 대략 45,000 km 상공이란 계산이 나옴. 이건 어디까지나 직선거리로 계속했을 경우인데, 과학 선생님과 대화 나누며, 내가 얼마나 기초 과학적 지식이 부족한 가, 즉 그렇지 않음을 알게 되었음. 직선으로 먼 거리로 물체를 쏘아올리려면 엄청난 힘이 필요하므로 지상에서 수직으로 4만 키로 올라간다는 것은 사실상 불가능함.)

Controllers at European Space Agency's Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany, expect to pick up a signal from the satellite not long after it has been released on to this cruise path, at 21:28 GMT.

The journey time to Mars is seven months. Three days out from arrival, on 16 October, the satellite will release a small landing module known as Schiaparelli.

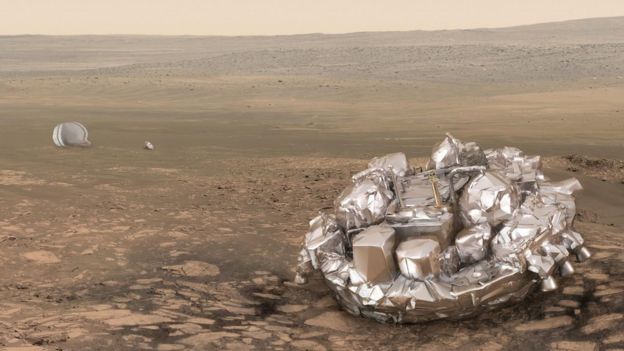

Once on the surface, on 19 October, its aim is to operate a few science instruments, but engineers are primarily interested to see how the module performs during the entry, descent and touchdown.

"This technology development is very important," said Esa's director of science, Prof Alvaro Gimenez.

"If you want to be a partner in the future on more missions to Mars, you have to demonstrate your ability to land. If you can't, you are not at the right level. We have to show we can do it ourselves."

Schiaparelli's demonstration landing on 19 October 화성 착륙예상 10월 19일

ESA

ESASchiaparelli will probably work for a couple of days - if it survives the landing - Schiaparelli will be released by the TGO close to Mars, on 16 October

- The probe will hit the top of the Martian atmosphere at a speed of 21,000km/h (the probe: 탐색기, 탐사선, 여기선 Schiaparelli를 의미하는 것으로 보임.)

- It will use a heatshield, parachute and rockets to slow its descent (heartshield: 이 말은 heart와 방패를 뜻하는 shield의 합성어, 정확한 의미는 모름) (parachute: 낙하산)

- The final touchdown will be cushioned by crushable material on its belly (crushion: 동사로 쿠션역할을 하다) (crushable: 찌그러질 수 있는) (belly: 복부, 여기선 중심부를 의미)

- The probe will take pictures on the way down, but it has no surface camera

- Schiaparelli will make environmental observations until its battery dies

- The main goal is to demonstrate its descent radar, computers and algorithms

- These will be used in the mechanism that lands the future ExoMars rover (rover: 방랑자란 뜻이나, 여기선 우주선을 의미하는 것으로 보임.)

In particular, Schiaparelli will showcase a suite of technologies - radar, computers and their algorithms - that will be needed to put a British-assembled rover safely on the planet.

This second-step ExoMars mission is supposed to leave Earth in 2018, although this looks increasingly in doubt.

No final price with industry to build the rover venture has yet been agreed, and there is currently insufficient money within the programme to fund it to completion. But even if the budget was not a problem, there is now so little leeway in the development schedule that few people express optimism that the rover and its associated landing equipment can be made ready in time for what is a very narrow launch window in 2018.

"It's now marginal," said Mr Cugno. "We have some possibility [of being ready] on the European side, but on the Russian side it is even more marginal."

A formal announcement of a delay to 2020 - when the planets next align - could come within a few weeks. But the difficulties with the rover part of the ExoMars project should not affect the orbiter.

ESA

ESAThe TGO and Schiaparelli (gold cone) being mated to the Proton rocket ready for launch Once it has dropped off Schiaparelli, the TGO will spend the better part of a year manoeuvring itself into a 400km-high circular orbit above the planet.

From this vantage point, the TGO's state-of-the-art instruments will then make a detailed inventory of Mars' atmospheric gases.

The mission is concerned with the components that constitute less than 1% of the planet's air - chemical species such as methane, water vapour, nitrogen dioxide, and sulphur dioxide.

Methane is the main focus. From previous measurements, its concentration is seen to be low and sporadic in nature. But the mere fact that it is detected at all is really fascinating.

The simple organic molecule should be destroyed easily in the harsh Martian environment, so its persistence - and the occasional spikes in its signal - indicate a replenishing source of the gas.

The explanation could be geological. one idea is that it is the simple by-product from water interactions with particular rock minerals at depth. Another explanation is that the gas is ancient in origin and has been trapped in sub-surface ice. Periodic melting events then release the methane into the atmosphere.

But there remains the tantalising prospect that the source could be biological.

Most of the methane in Earth's atmosphere comes from living organisms, and it is not a ludicrous suggestion that microbes might also be driving emissions on Mars.

"Whatever the explanation, it all points to the existence of liquid water in the sub-surface, and that changes slightly our vision of Mars, because it means it is a planet that is a little more active than we've recognised," said Esa's ExoMars project scientist, Dr Jorge Vago.

The TGO instruments will try to describe the methane's distribution in time and space.

Two of its sensors - NOMAD and ACS - will determine the gas molecules' concentration across the seasons, at different altitudes and locations.

A third instrument, the CaSSIS camera, will then look for possible geological forms on the surface of the planet that might tie into methane sources. A fourth instrument, FREND, will sense hydrogen in the near-surface. This data can be used as a proxy for the presence of water or hydrated minerals. All of this is information that could yield answers to the methane question.

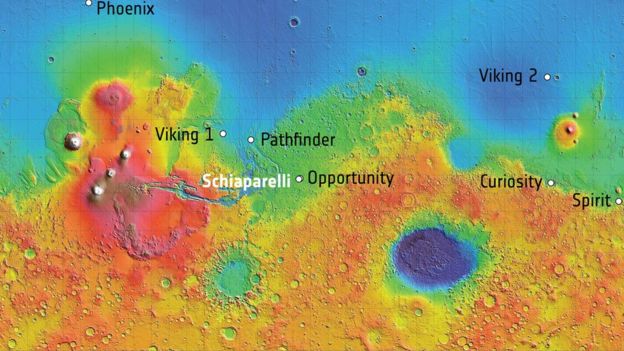

MOLA

MOLASchiaparelli is being targeted at Meridiani Planum - the same place as Nasa's Opportunity rover  ESA

ESAArtist's impression: The likelihood of the ExoMars rover being sent to Mars in 2018 is diminishing '과학과 테크놀로지 > 과학' 카테고리의 다른 글

(과학) Equinox (주야평분시/晝夜平分時) (0) 2016.03.27 (과학) 거미는 거미줄의 진동을 통해 먹이감을 파악해 잡아먹는다 (0) 2016.03.19 [스크랩] [카드뉴스] 아인슈타인의 마지막 예언도 적중했다 (0) 2016.02.12 (과학) 숫자는 중력파를 정확히 보여주지 않는다 (0) 2016.02.12 (과학) 아인슈타인의 중력파 관측되다 (0) 2016.02.12