- 4 August 2016

- Science & Environment

-

(과학) 뇌의 '갈증담당 회로'가 입안을 모니터한다과학과 테크놀로지/과학 2016. 8. 8. 18:56

출처: http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-36966275

Brain's thirst circuit 'monitors the mouth'

THINKSTOCK

THINKSTOCKLow temperatures apparently shut down the same neurons that generate thirst Scientists have glimpsed activity deep in the mouse brain which can explain why we get thirsty when we eat, and why cold water is more thirst-quenching.

A specific "thirst circuit" was rapidly activated by food and quietened by cooling down the animals' mouths. 이번 연구는 뇌 속의 특별한 "갈증담당 회로"가 음식에 의해 급격히 활성화되거나 동물의 입안의 더위를 식혀줌으로써 (그 회로가) 활성화되었음을 보여주었다.

The same brain cells were already known to stimulate drinking, for example when dehydration concentrates the blood.

But the new findings describe a much faster response, which predicts the body's future demand for water.

The researchers went looking for this type of system because they were puzzled by the fact that drinking behaviour, in humans as well as animals, seems to be regulated very quickly.

Pre-empting demand

"There's this textbook model for homeostatic regulation of thirst, that's been around for almost 100 years, that's based on the blood," said the study's senior author Zachary Knight, from the University of California, San Francisco.

"There are these neurons in the brain that… generate thirst when the blood becomes too salty or the blood volume falls too low. But lots of aspects of everyday drinking can't possibly be explained by that homeostatic model because they occur much too quickly."

Take the "prandial thirst" that comes while we consume a big, salty meal - or the fact that we feel quenched almost as soon as we take a drink.

Thirst, Dr Knight explained, often pre-empts changes in our fluid balance rather than responding to them.

And his team's experiments, reported in the journal Nature, offer the first explanation for how that anticipation might be generated within the brain.

KNIGHT LAB, UCSF

KNIGHT LAB, UCSFRecordings were made in mice that were moving - and drinking - freely To unpick the brain activity involved, the researchers monitored neural activity in genetically engineered mice. Deep in these animals' brains, a specific type of brain cell - in an area known to regulate thirst - would glow when it was active.

This meant the team could use an optical fibre to record how busy those neurons were, while the mice were left to eat or drink in various experimental conditions.

Cold power

When the animals were thirsty, these brain cells (in a region called the subfornical organ, or SFO) were very active. As soon as they drank, that activity dropped.

Similarly, the "thirst circuit" lit up when the mice ate - much faster than any measurable changes could be detected in their bloodstream.

These SFO neurons were responding directly, it seemed, to the goings-on in the animal's mouth.

"The activity seems to go up and down very rapidly during eating and drinking, based on signals from the oral cavity," Dr Knight told the BBC.

Perhaps most remarkable was the effect of temperature, he added.

"Colder liquids inhibit these neurons more quickly. In fact, we show that even simply cooling the mouth of a mouse is sufficient to reduce the activity of these thirst neurons - independent of any water consumption."

The idea that the thirst system is monitoring mouth temperature - to the extent that applying a cool metal bar to a mouse's tongue will light up these SFO neurons - makes a lot of sense, Dr Knight said.

"If you go into the hospital and you can't swallow, they give you ice chips to suck on, to quench your thirst.

"Temperature seems to be one of the signals that these neurons are listening to."

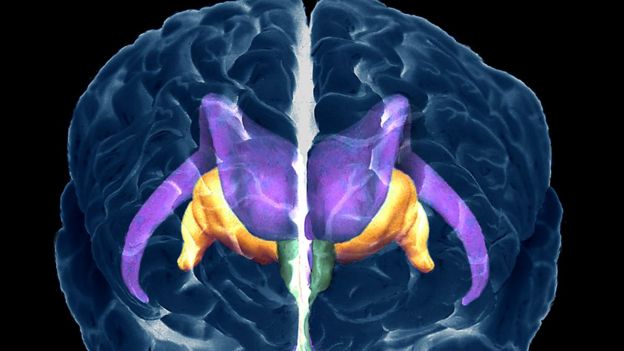

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARYIn the human brain, the corresponding neurons sit just above the hypothalamus (shown in green) Dr Yuki Oka, a neuroscientist at the California Institute of Technology, was not involved in this research but led a previous study on the same population of SFO neurons.

His team discovered that artificially stimulating these thirst neurons caused mice to drink, even if they weren't thirsty - a finding that Dr Knight and colleagues replicated as part of their work.

Dr Oka said the new observations were very interesting, particularly because they showed how one population of brain cells was combining different types of information.

"The previous view in the field was that [this system] is monitoring... the internal state. But recent studies - including this one - are showing that these sensory neurons in the brain are not just a sensor, they're an integrating platform for the external stimuli and the internal state.

"This is kind of a new concept, which has also been revealed in neurons that control feeding."

'과학과 테크놀로지 > 과학' 카테고리의 다른 글

(과학) 수면은 우리가 신경쓰는 문제의 순서를 매긴다 (0) 2016.09.10 (과학) 지질학자들 인류세의 '골든 스파이크' 탐색하다 (0) 2016.09.02 (과학) 슬로모션 재생은 형사책임을 왜곡시킬 수 있다 (0) 2016.08.03 (과학) 타이타니움보다 4배 견고한 초강력 물질은 금과 타이타니움의 합금 (0) 2016.07.31 (과학) NASA 탐사선 주노(Juno) 목성 궤도에 진입 (0) 2016.07.08