- 3 hours ago

- Magazine

-

(자아성장) 지혜로운 사람이란 있는가?사람되기/성장 2016. 1. 3. 12:41

출처: http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-35171476

A Point of View: Is there any such thing as a wise person?

iStock

iStockAn orgy of Shakespeare celebration is about to occur. The bard can tell us a lot about what it means to be wise, writes Howard Jacobson.

As we'll soon be putting our Three Wise Men away in their boxes for another year, it might be a good time to talk about wisdom generally. It is also, 2016 being the four hundredth anniversary of his death, a good time to talk about Shakespeare. But then when isn't?

"Get wisdom," says the Bible, "and with all thy getting get understanding." It's hard to take issue with that, except to wonder how you go about getting it. Where? How? And when do you know you have got it?

"I hear you're reputed to be funny," a reader told me sniffily at a book-signing not long ago, "but I think you're wise."

Her emphasis was on "I", as though to say "though I'm sure no one else does". I smiled at her cautiously. Signings are dangerous occasions. You never know who wants to pay you back for some obscure wrong with sarcasm. But even if she meant this praise sincerely, I felt undeserving of it. Wise? Me? And then I had a second, more irritable thought - was "wise" even a description I welcomed?

There is something aging about wisdom. Say you met a wise man on your travels and people will immediately picture an elderly, humourless sage living in a cave.

The word encompasses not just notions of longevity but also emaciation. Maybe Asian wisdom can be plump, but in the west we like the wise to be skin and bones. Something to do with renunciation. You can't be wise and not renounce, and you can't renounce and not be thin.

I always think of Hamlet's friend Horatio as thin. "A man that Fortune's buffets and rewards / Has ta'en with equal thanks" is how Hamlet describes him condescendingly. It means he has wisely renounced vanity, ambition and anger, which Hamlet himself of course hasn't.

Were I Horatio, I wouldn't like the compliment Hamlet pays me. Who wants to be praised for being old before one's time?

The young are not meant to be phlegmatic. They should be profligate with their passions. It's wisdom - that asset of old age - that teaches us to hold back. When we say a man is wise with his money we mean he is tight-fisted.

We don't think of a wise man as having gargantuan appetites, a love of finery or a huge capacity for time wasting. Cave or no cave, he won't own a wardrobe of silk ties, a well-stocked cocktail cabinet or a 62-inch television. And foremost among the pleasures he has renounced is sex. Whoever spoke of a wise lover? The wiser the lover, the longer ago he stopped loving.

Horatio (left) has achieved a measure of wisdom If the wise man is not, in our mind's eye, young, neither is he, in our mind's eye, happy. When we speak of a man who has made a success of his marriage we call him a good husband, not a wise one. Similarly, we speak of good fathers and good friends. A wise friend might well be one who decides it's better, all things considered, not to be your friend at all.

Having turned their backs on everything the rest of us are still interested in, the wise are chilly. We can't imagine wisdom being cited among the qualities most desired by people looking for romance. Great sense of humour, yes. Bubbly personality, yes. Along with tolerance, broadmindedness, a love of Thai food and country walks, an enthusiasm for the songs of Amy Winehouse, and a liking for box sets. But wisdom?

"Beyonce lookalike wanted, wisdom essential...? Bubbly divorcee into box sets seeks her Solomon for long evenings of sagacity..."

But even were wisdom a commodity suddenly to be in demand, it would still shame all but the most immodest of us to be accounted wise because wise is the last thing we know ourselves to be. Wise? Us?

The great French essayist Montaigne famously enumerated the diversities of his nature, describing himself, with Hamlet-like self-distaste, as: "Shamefaced, bashful, insolent, chaste, luxurious, peevish, prattling, silent, fond, doting, laborious, nice, delicate, ingenious, slow, dull… ignorant, false in words, true-speaking, both liberal, covetous, and prodigal."

I'm surprised he leaves out proud, revengeful, ambitious, clumsy, splenetic, quick to judge and slow to learn. Speaking for myself, I choose the wrong clothes to buy and the wrong food to eat. I lose my temper with people who have done me no harm and pay inordinate compliments to people who have done the world no good. I forget the names of those I know and am overfamiliar with those I don't.

PA

PAThe Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee is often referred to as the Wise Men My consolation is that I don't only have Montaigne for company. "Alas! 'tis true, I have gone here and there, / And made myself a motley to the view" - Sonnet 110. It helps to know that Montaigne considered himself peevish and prattling, and Shakespeare felt he'd played the indiscriminating clown.

Of course a sonnet is not a confessional. A sonnet is a dramatic form, and it is no more legitimate to suppose that Shakespeare is talking from the heart of his own folly in Sonnet 110, than it is to suppose that he is talking from the depths of his own desolation when he has Macbeth describe life as a tale told by an idiot. Part of what makes Shakespeare so great a writer is that he doesn't burden us with what he thinks.

But there are too many scenes in the plays where characters speak slightingly of themselves - take "I am a very foolish, fond old man" - for us to doubt that Shakespeare knew as well as any man the ignominy of acting without sense or circumspection.

Here is something more valuable than wisdom - an acceptance that one doesn't have any. We might be tempted to say that Shakespeare strikes a note of acceptance in the late plays - a mature, half-sad reflectiveness, that feels like wisdom.

But we don't call Macbeth a wise play because the dramatic means by which it comes to know of torment are too active to go by the name of wisdom. The play goes on discovering its own subject in the very process of enacting it. So yes, get wisdom, but better still get what Shakespeare got.

Getty Images

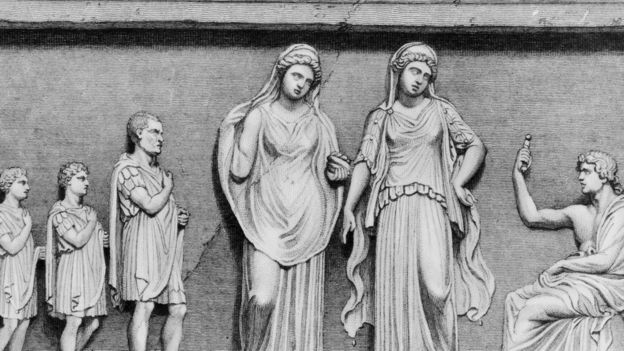

Getty ImagesThe sibyls at Delphi were the ancient Greeks font of wisdom but they claimed to channel the supernatural What's wrong with wisdom is that it implies stasis, as though our greatest faculties of cognition and intuition are at their journey's end, and have attained a peak of complacency from which they gaze down imperturbably on the small vanities of man.

But look again, in the light of Shakespeare, at what the Bible enjoins - get wisdom, and with all thy getting get understanding - and it suddenly looks more challenging. It demands not that we be wise, but that we get wisdom.

The knotty sentence - get and with all thy getting get - suggests an almighty struggle, a striving not an arriving. And more than that, wisdom isn't its own end either. Understanding still awaits. And understanding isn't knowledge or assertiveness but a process, never over, never done with, a million miles from those brute asseverations of certainty which are the living curse of our new cyber-world and make half-fanatics of all who inhabit it.

Coleridge wrote of Shakespeare's imagination "kindling like a meteor... one sentence begetting the next naturally... the meaning all inwoven". Weaving, kindling, getting, begetting - these are verbs of creative process.

We don't go to Shakespeare for wisdom. The wise in Shakespeare are sententious old fools like Polonius who say "to thine own self be true" and "neither a borrower nor a lender be".

But the imagination - which stumbles on what it knows, not knowing it in advance, and where meaning begets meaning - this is the dynamism of art, alongside which wisdom, though it might belong to the family of intelligence, is but a poor relation.

So I was right not to feel complimented when a reader called me wise. Better to be described as someone who gets and garners understanding in the act of discovering he knows nothing.

'사람되기 > 성장' 카테고리의 다른 글

(자아성장) 11명 여성들이 말하는 섹시함에 대해: Beauty Has No Age Limit. (0) 2016.03.03 (자아성장) 미즈넷: 남편에게 너무 미안하고 고마워요 (0) 2016.02.14 (자아성장) 넔을 잃을 만큼 잘난 외모의 명암 (0) 2016.01.01 (자아성장/동영상) 제902회 남편이 처가에 대해 적대적이고 인색해요 (0) 2015.12.28 (자아성장/동영상) [법륜스님 즉문즉설 1141회] 결혼하고 싶은데 아버지에 대한 기억으로 두렵습니다 (0) 2015.12.20