- 7 hours ago

- India

-

(아시아/인도) 인도 배후의 어두운 역사와 영국이 즐기는 음료국제문제/아시아 2016. 7. 16. 01:35

출처: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-36781368

The dark history behind India and the UK's favourite drink

Is this the best cup of tea in the world? This is the extraordinary story of the most ubiquitous and familiar Indian street food of the lot. (ubiquitous: 흔한)

I say street food, but this is actually a drink, and it is no exaggeration to say it was one of the great engines that drove the globalisation of the world economy.

It caused wars and boosted the trade in slaves and hard drugs.

The conditions it is produced under are still so bad that the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge decided not to include it in their recent tour of India.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESTea's toxic history persuaded the Royal couple to change their India plans Yet it is enjoyed in every country on earth, with India the biggest consumer of them all.

And that should be no surprise, because although this product doesn't come from India, the country has been instrumental in its rise to global popularity.

Yes, you've guessed it, today we are drinking tea.

This is the 12th article in a BBC series India on a plate, on the diversity and vibrancy of Indian food. Other stories in the series:

Why this Indian state screams for ice cream

The street food that silences even the most heated debate

How home chefs are helping uncover India's food secrets

Amma canteen: Where a meal costs only seven cents

But because this is India, this is tea with a little extra added: this is masala chai.

Masala simply means spice. No Indian can live without masala in their lives.

We'll talk about that later, for the moment let's focus on the "chai" bit and discover how India - and the world - developed its taste for tea.

Chai is the word for tea in Hindi and most other Indian languages, and it begins our journey, because the word itself betrays the original source of these aromatic leaves.

Its root is the Mandarin word chá.

But the story of how India got its taste for what was originally a Chinese product is far from straightforward.

AFP

AFPThis shop sells a cup of tea for as little as eight rupees (12 cents) Indeed it was the popularity of another commodity - itself first refined in India - that would get the world hooked on tea.

The Chinese had been drinking tea for millennia and tea was one of the first new goods Dutch merchants brought back from their trips to the Far East way back at the beginning of the 17th century.

The drink quickly became popular, first as a medicine and then as an exotic new menu item in the coffee shops of European capitals, making its way as far as New Amsterdam (New York).

Its popularity grew steadily but for the next century this fragrant but bitter brew was to remain a rare and expensive treat enjoyed only by the elite.

AFP

AFPIndian tea is made with milk and sugar And so it might have remained had the Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors not taken sugar cane to the New World.

Indians were the first to develop a process to produce crystals of sugar, way back around the time Jesus was preaching in Judea. 결정체 설탕을 세계최초로 생산한 건 예수가 유대에서 활동하던 당시의 인도인들. (2천년 전)

They used juice squeezed from the stems of the sweet grass that had been grown in Asia for thousands of years. 사탕수수에서 즙을 짜서 먹던 역사는 아시아에서 수 천년 역사.

But it was only with the establishment of vast sugar cane plantations in America and the Caribbean, based on the sweat and toil of slaves brought from Africa, that sugar began to be produced on a large scale.

For the first time it became increasingly plentiful and cheap in Europe.

But how to consume this delicious new product?

Someone somewhere had the idea of mixing a spoonful or two into a cup of tea. 차에 설탕 섞어 마심.

Then it became fashionable to add milk too. 거기다 우유도 타서 마심.

Suddenly what was a drink for connoisseurs became something everyone could enjoy.

This process of "domestication" led to an explosion in the popularity of both tea and sugar.

And if Europe's taste for sweet tea helped underpin the slave trade between Africa and the Americas, it was just as destructive on the other side of the world. 유럽인이 달콤한 차를 선호하는 유행이 아프리카와 아메리카 사이 노예무역을 촉진시켰다면, 이건 그 세계의 나머지를 황폐하게 만들었다는 얘기.(?) (underpin: 뒷바침하다)

AFP

AFPMillions of Indian begin their day with drinking tea It is worth retelling the story of the Opium Wars because they could just as well be called the Tea Wars - they were at least as much about this mild stimulant as they were about the narcotic drug.

That's because in the 18th century tea was grown exclusively in China.

Britain was buying huge quantities of the stuff - it was top of the national shopping list above other exotic Chinese goods like silk and porcelain.

The problem was the Chinese didn't reciprocate. (reciprocate: 화답하다. 응답하다)

They weren't too keen on anything produced in the rainy little island that was the centre of the European tea trade.

Then, as now, this was a recipe for economic disaster.

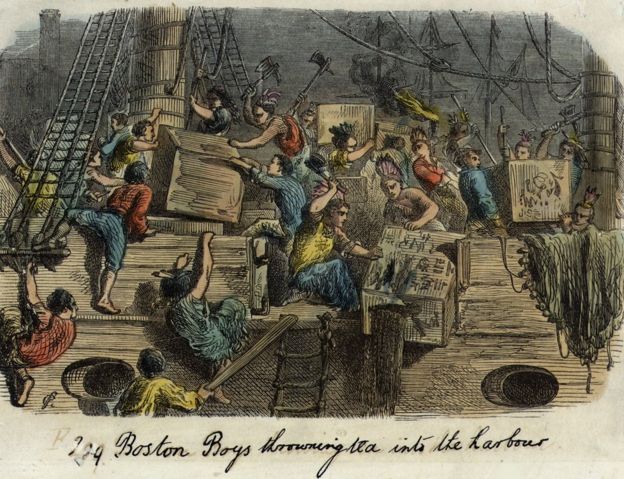

When the British tried to manipulate the market, the colonists in America - another booming market for tea - were not pleased.

They famously tossed a shipload of the stuff into Boston harbour, marking the beginning of the end of British control in America.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESThe Boston Tea Party marked the beginning of the end of British control of America And it wasn't just restive colonists that were getting upset, Britain's taste for tea was well on the way to bankrupting the entire nation.

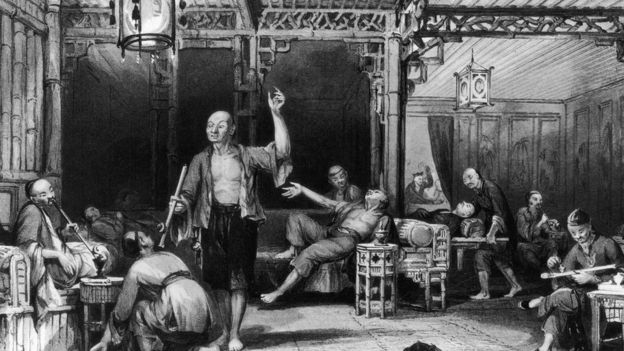

Until, that is, the East India Company, which had a monopoly on trade with the Far East, found a product that Chinese did want to consume - opium.

It took control of the market for opium in the Indian state of Bengal, encouraging farmers to grow more, rationalising production and developing new cultivation techniques.

When the Chinese made the trade in opium illegal the Company sidestepped the ban by auctioning its opium off to smaller traders who smuggled it to China.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESThe British "negotiated" a humiliating peace with China When the Chinese emperor protested that the drug was creating millions of addicts, he was ignored.

But when, in 1839, he confiscated some 20,000 chests of opium, the British took action.

There was little discussion in the mother of parliaments about what needed to be done.

Gunboats with a small army were rapidly dispatched to sort the problem out.

Their superior arms and equipment ensured a speedy victory for the British who then "negotiated" a humiliating peace with China.

They forced the Chinese to open up ports to British trade in everything - including opium - and to cede the island of Hong Kong to the Crown to boot (it was only returned in 1997).

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESThe Opium trade in China was because of tea Meanwhile, though, the bosses of the East India Company were already working on a plan to avoid future disruption of the tea market.

And, once again, India was the obvious place to start.

In the 1830s, the first tea estates were established in the Indian state of Assam, using tea plants brought from China.

Just like sugar, growing tea is very labour intensive and the obvious thing would have been to staff them with slaves.

But in 1833, slavery was banned in the British Empire.

Those clever men at the East India Company needed to find an alternative - and they did.

Instead of slaves, tea estates used indentured labourers, free men and women who signed contracts binding them to work for a certain period.

But the truth is conditions for these workers weren't much better than for slaves.

What is more shocking still is the fact that many of the practices and traditions established way back when the estates were first planted continue even on estates that supply some of the world's favourite brands, as I discovered last year in an investigation for BBC News.

That investigation persuaded the team organising the British Royal couple's tour of India in April this year that a visit to a tea estate would not be advisable.

Appalling conditions aside, pretty soon India had become the biggest supplier of the strong black teas now favoured in Britain and Europe.

At first, this valuable commodity was strictly for export, but as production grew and the price fell, Indians began drinking tea too.

And, naturally enough, they followed the example of the British and drank their tea with milk and sugar.

Which brings us back to the masala chai that first prompted this reflection.

It may have its origins in the drink an English vicar might serve parishioners on a sunny afternoon on the parsonage lawn, but it has been transformed by some subcontinental adaptations and improvements.

AFP

AFPIndians often add pounded ginger and crushed cardamoms to tea First off, it is much stronger, milkier and sweeter than any British brew.

Chai walas - the artists who make masala chai - boil strong black tea hard with milk, water and lots and lots of sugar until it is almost a syrup.

Good ones will add a good fistful of pounded adarak - ginger - and, right at the very end, a couple of crushed cardamoms.

More adventurous tea stall owners may even add cinnamon and pepper.

The resulting sweet, spicy liquor will be drained through a sieve and served piping hot in a tiny glass or, more fun still, an unfired earthenware cup which you get to smash once you've finished your delicious and reviving dose of chai.

So why not get yourself up a cup of tea and relax?

I'm not expecting you to think about tea's dark history whenever you drink the stuff - that would be too much to ask.

But every now and then, do take a moment to reflect on the momentous global interactions that made the drink you are enjoying possible.

AFP

AFPSometimes, tea is served in clay cups in India Because, it reminds us that that although the growth of international trade has brought untold wealth to the world, globalisation virtually always leaves victims in its wake.

And to drive that point home, what I haven't yet mentioned is the reason the Chinese had such an appetite for opium.

They had adapted the tobacco pipes brought to Asia from the New World and now used them to smoke opium too.

The result was a far stronger, and far more addictive, hit.

By the turn of the 20th Century, Britain had become the biggest drug dealer the world had ever known, and China had developed the biggest drug problem experienced by any nation ever.

According to official figures, in 1906, 23.3% of the adult male Chinese population was addicted to opium.

'국제문제 > 아시아' 카테고리의 다른 글

(아시아/인도) 부르한 와니의 사망에 격분한 카슈미르 시위로 36명 사망 (0) 2016.07.23 (아시아) 캄보디아와 한국의 2015년도 1인당 GDP 비교 (0) 2016.07.17 (아시아) 남중국해 영토분쟁: 중국 국제사법재판소 판결에 불만 (0) 2016.07.13 (아시아) 국제사법재판소 필리핀과 중국間 남중국해 분쟁 판결 예정 (0) 2016.07.12 (아시아) 탈북 식당 여종업원을 법정에 세운 것은 흔하지 않은 경우 (0) 2016.06.22